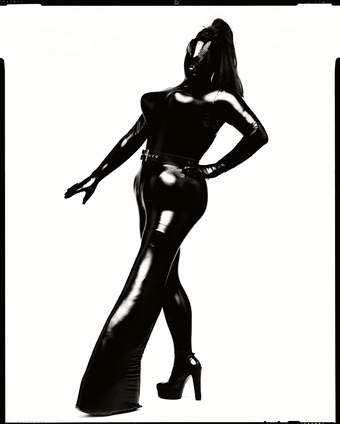

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session I Look 2 1988

© Fergus Greer

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Modern

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session I Look 2 1988

© Fergus Greer

Leigh Bowery (1961–1994). A smalltown boy from Sunshine, a Melbourne suburb in Australia. He’s bored. Inspired by the punk scene, Bowery leaves fashion college and arrives in London in October 1980. The New Romantics hold court. That December, he writes his New Year resolutions:

This would be just the beginning of Bowery’s aspirations.

In his brief life Bowery was described as many things. Among them: fashion designer, club monster, human sculpture, nude model, vaudeville drunkard, anarchic auteur, pop surrealist, clown without a circus, piece of moving furniture, modern art on legs. However, he declared if you label me, you negate me and always refused classification, commodification and conformity. Bowery was fascinated by the human form and interested in the tension between contradictions. He used makeup as a form of painting, clothing and flesh as sculpture, and every environment as a ready-made stage for his artistry. Bridging the gap between art and life, he took on different roles and then discarded them, presenting an understanding of identity that was never stable but always memorable.

Bowery embraced difference, often using embarrassment as a tool to release both his own inhibitions and those of people around him. He wanted to shock with his ‘Looks’ and performances. At a time of increasing conservative values in Britain, Bowery refashioned ideas around identity, morality and culture. At times this caused offence.

This exhibition traces Bowery’s beginnings as a fashion designer and club kid in the nightlife of 1980s London, through to his later performances in galleries, on the stage, the street and beyond, until his death in 1994. It is a journey into the dynamic creative scene inhabited by Bowery and friends.

From the late 1970s, the underground culture of the New Romantics had been at the forefront of London’s club scene. Inspired by glam rockstars like David Bowie, Slade and Roxy Music, this flamboyant style often defied gender conventions. By the time Bowery arrived in London in 1980, however, New Romantic style had started to change. People on the scene began to adopt the ‘Hard Times’ look, wearing garments with dull colours and frayed edges. For his first fashion collection, Bowery created his own version of this look, made with meagre funds saved while on unemployment benefit.

In 1984 he shifted gear, developing a collection that featured brightly coloured clothes made from shiny synthetic fabrics, sequin-covered vinyl hats and platform boots, with models’ faces painted different colours. The collection combined his range of interests: sci-fi, astrology, glam rock (then considered out of fashion), Hindu deities, as well as garments worn by the Bangladeshi community in East London (where Bowery was living). In other designs, he used cut-aways and ruched fabric to emphasise different parts of the body. He used makeup to create a variety of abstract shapes or imitation scabs and warts.

Bowery’s artistry extended to his living environment, which he created with his best friend, the artist Trojan. With little resources, they transformed their home into a capsule that continued their interest in bad taste, exaggerated forms and the other worldly. Charles Atlas’s video in this room shows Bowery and friends in their flat as they get ready to go out clubbing. Some of Bowery’s garments from different fashion collections are on display here, alongside personal items, sketchbooks and photographs from his early years in London.

The most fashionable place to see-and-be-seen is Taboo on Thursday. The policy is simple. Dress as though your life depends on it, or don’t bother.

Time Out

It took time for Bowery to find his people. In 1981, a chance encounter with drag queen Yvette the Conqueror took him to the The Cha Cha Club in the back room of Heaven, the UK’s biggest gay nightclub at the time. It opened a world to him. However, it was only when Bowery, Trojan and designer David Walls went out together wearing Bowery’s designs that he solidified his position on the scene.

The 1980s was the era of club culture – no social media, only hand-made or word-of-mouth invites. IYKYK. Clubs represented an underworld of queer revelry where creatives belonging to various subcultures came together. It was a way of testing out ideas, being inspired by what others were wearing, then reading about it in the new style magazines i-D, The Face and Blitz.

By 1983, Bowery was showing his fashion collections internationally. Soon, though, he decided that he was more interested in creating designs for his own body and for a select clientele rather than for the general public. London’s nightclubs became the catwalk for his creations.

In 1985, Bowery and promoter Tony Gordon set up Taboo – an ironically named club because you could do anything there. It soon became known as London’s sleaziest, campest and bitchiest club of the moment. On the door, Marc Vaultier would hold a hand-mirror up to badly dressed punters and ask: Would you let yourself in? Taboo remained open for a little more than a year before it was shut down due to tabloid accusations of drug-taking on the premises. Soon after, Bowery’s Looks became increasingly elaborate, covering his whole body with fabric, featuring more sequins, and exaggerating proportions to draw attention to himself.

I like the [Looks] to be as strong as they are, especially now that everyone’s being so conservative and austere. I don’t want the things I make to be merely flamboyant; that’s been done before. … It has to have that edge, you know, because if I’m laughing at the way I’m dressing myself … what possible criticism can people make, really? If the joke’s on me and I know it?

Leigh Bowery

Humour was a dominant feature of Bowery’s Looks, as well as being central to the way he performed and acted when wearing them. When he appeared on catwalks and TV shows, he used parody and slapstick to disrupt established conventions of fashion, high society and culture. This extended to his personal life, where he often spread rumours to wind people up. When asked by a journalist: On what occasions do you lie? Bowery responded: On what occasions do I breathe? Bowery’s brand of humour and innuendo was shared by eccentric TV personalities of the time, from the likes of Quentin Crisp and Kenneth Williams to Dame Edna Everage and Lily Savage.

In the art world, Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World provided Bowery with another way to consider dressing up as a performance. First created in 1972 and still ongoing, the competition reimagined the Miss World beauty pageant to celebrate the art of transformation. Contestants present daywear, swimwear and eveningwear looks, and are judged on the same criteria as the Crufts Dog Show: POISE! PERSONALITY! ORIGINALITY!

Bowery first met many of his London friends after attending the 1981 Alternative Miss World. He would later participate in (and fail to win) the 1985 and 1986 competitions. The 1986 event was meant to take place at Chislehurst Caves in Kent, but was banned by the police after the local community raised concerns that it would spread AIDS. Instead, it went ahead at Brixton Academy, London.

Yes to spectacle.

Yes to virtuosity.

Yes to transformations and magic and make-believe.

Yes to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

Yes to the heroic.

Yes to the anti-heroic.

Yes to trash imagery.

Yes to the involvement of the performer or spectator.

Yes to style.

Yes to camp.

Yes to seduction by the wiles of the performer.

Yes to eccentricity.

Yes to moving or being moved.Michael Clark, YES Manifesto, 1984

A response to artist/choreographer Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto, 1965 and First Lady Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No anti-drugs campaign, 1982

Fergus Greer Session VII, Look 38, June 1994 1994, printed 2025 © Fergus Greer, courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London.

Bowery found a more prominent stage for his imagination when he started to design costumes for choreographer and dancer Michael Clark in 1984. Clark was a key figure on the scene. Classically trained in ballet, he injected the dance world with a lightning bolt of energy, bringing in references to punk, gay sexuality, club culture, musical theatre and Scottish Highland dancing. Clark’s interest in punk chimed with Bowery, who said it had prompted his own move to London.

Soon becoming close friends, Bowery designed costumes for the Michael Clark Company from 1984 to 1992. Clark gave free reign to Bowery, remarking that traditional costume designers were too ‘accommodating’.

The dance sequences in Charles Atlas’s film Hail the New Puritan 1986 showcase the range of Bowery’s designs for Clark. Featuring frilly underwear, exposed bums and chests, elements of glam rock and deconstructed tailoring, the designs echo Clark’s anarchic spirit.

Bowery’s natural flair for movement and comic timing led him to appear in several Clark productions from 1985 to 1992. Clark’s show Because We Must 1987, filmed by Charles Atlas in 1989, features Bowery in a range of Looks as he plays the piano, performs skits with dancer Les Child and participates in the dance routines. Bowery’s designs for the Michael Clark Company highlight his continued interest in exaggeration and camp sensibility, which were complemented by the additional costumes by fashion designers BodyMap, who also frequently collaborated with Clark.

I can’t really tell the difference between a stage and a street.

Leigh Bowery

Bowery’s everyday look was just as fascinating as his club and stage clothes: bad wigs, tatty jumpers, heels in clogs hidden by baggy trousers, one eyebrow taped up to create a wonky appearance. He said he wanted to look like the weirdo on the street that you tell your mum about. At times Bowery would wear these outfits while cruising for sex in public toilets and parks.

Every environment, including the street, was a potential stage for Bowery’s exhibitionism and desire to subvert ‘normality’. On one occasion police arrested him for putting on a show in the middle of the road. Using car headlights as spotlights, he performed on the street while wearing an all-nude outfit save for a merkin (pubic wig) and headpiece.

Bowery extended his peculiar brand of normality to the styling for the music video ‘Generations of Love’ 1990 by Boy George’s band Jesus Loves You. Directed by Bowery’s friend Baillie Walsh, it features Bowery and friends playing sex workers as they run through the streets of Soho and pop into a porn cinema.

The street was also the set for Bowery’s photo-work Ruined Clothes 1990. Bowery and his friend, fashion designer Nicola Rainbird, threw garments ruined on previous nights out from the balcony of Farrell House, then photographed them. The works were shown at an exhibition in Tokyo, along with the real garments on the floor. Bowery also did a performance. Ruined Clothes provided a way for Bowery to view his creations when they weren’t on his body, demonstrating their status as a second skin.

A gallery, divided in two by a wall with a large two-way mirror. Bowery appears on one side under a spotlight, only able to see his reflection. On the other side, the audience watches. Sounds of insects and the street outside can be heard. Different scents, like banana and marshmallow, fill the room.

This was the set up of Bowery’s first performance in a gallery. In October 1988, he posed at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London for two hours each day, across five days. He wore a new Look every day, selected from those he had worn over the last four years. The spots suit, checkerboard dress, and green feathery jacket were remade by designer and corsetier Mr Pearl (some of which are displayed in Room 2) due to the originals being covered in ‘disco dirt’. Bowery worked closely with the gallerist Lorcan O’Neill, who had invited him to perform, the artist Cerith Wyn Evans who also filmed and edited the video documentation, and DJ Malcolm Duffy who worked on the sound.

In the ‘Mirror’ performance Bowery staged the very act of looking, treating his body as an art object. Les Child described the performance as You watching me, me watching me and many people remarked it was as much about the visitors in the space as Bowery himself. Dick Jewell’s video What’s Your Reaction to the Show? 1988 captured viewers’ responses as they left the gallery.

Soon after the performance Bowery began an extensive portrait project with the photographer Fergus Greer, carefully documenting many of Bowery’s key Looks.

In November 1988 Bowery was diagnosed with HIV, a fact he would keep to himself, only telling his friend Sue Tilley and later Nicola Rainbird.

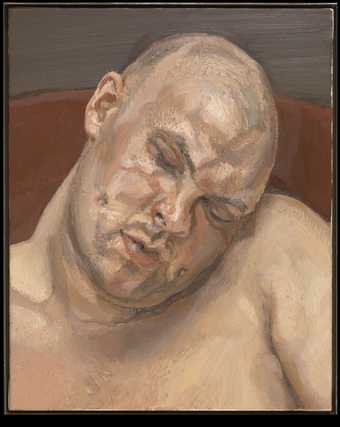

Lucian Freud Leigh Bowery 1991 © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Flesh is the most fabulous fabric. I like to camouflage my body because by concealing you can reveal, but you can also do the reverse.

Leigh Bowery

As Bowery entered the 1990s, he moved away from adding sequinned embellishments to his outfits. Continuing to create his designs in his home-studio, Bowery worked with Mr Pearl and new assistant Lee Benjamin to produce Looks that used foam, stretch fabric and latex to distort his body into a surreal, and at times alien-like, creature. Increasingly he considered his creations to be stand-alone artworks, and he was photographed and filmed by artists in studios and on the street to create performances solely for the camera. Bowery’s live performances became more shocking and extreme, influenced by the alternative drag and queer scenes in New York – at clubs like Jackie 60 and The Pyramid Club – and avant-garde performance artists.

During this time Bowery began to pose for painter Lucian Freud. Bowery had met Freud at Taboo through his friend Angus Cook. He was then re-introduced by Cerith Wyn Evans after the ‘Mirror’ performance. Freud painted Bowery on a larger scale than usual for his portraits. The works highlight Freud’s continued fascination with how paint can be used to depict the reality of flesh and being. Bowery appears ‘unmasked’, for once without makeup and clothing. But are these works the real Leigh? Or just another performance?

Bowery and Freud formed a close bond, relishing each other’s shocking stories. Bowery in particular was inspired by the painter’s refusal to conform to societal demands. Posing for Freud involved multiple sittings, as the artist worked on the paintings over a long period. As Bowery became increasingly in demand abroad, he roped in his friends Sue Tilley and Nicola Rainbird to pose so he would still be connected with Freud’s world. Rainbird later made a top from Freud’s paintbrushes.

When in doubt, go out.

Jeffrey Hinton

The club continued to be a place for Bowery to show off his Looks, stage performances and provoke a reaction. This room features a bespoke multimedia installation by Jeffrey Hinton, who was the main DJ at Taboo. Videos and animated photographs are from Hinton’s vast archive, and he has created the collaged soundtrack from music he played at the club, accented with various light effects.

The videos mimic the ‘scratch videos’ Hinton would show at Taboo. Such films were part of an experimental video movement that featured layered images and quick edits, disrupting the cohesion of mass media imagery. Hinton often included material ripped from various sources including pornographic films, videos of surgical operations, TV commercials and music videos. A portrait of Bowery and Taboo, the installation is inspired by the layered aesthetic of Bowery and his friends’ work, evoking how they created their own world in all of its messy, provocative complexity.

Bowery appeared at clubs in cities internationally, including London, Paris, Amsterdam, Bologna, Tokyo and New York. Among the many London clubs and nights he frequented were Kinky Gerlinky, The Fridge, Bar Industria and The Beautiful Bend at Central Station. The ecstatic and provocative energy of Bowery’s presence is captured here in videos by John Maybury and Dick Jewell. Gordon Rainsford’s photos show one of his most controversial performances, which took place at The Fridge in Brixton.

In all the things I’ve done over the last 10 years, the body has been the central thing. It’s like the imagination, it’s anything, it’s endless, there’s so much you can do. The more I become involved with people who do body manipulation and all kinds of performances the more exciting it becomes.

Leigh Bowery

On Friday 13 May 1994, Bowery and Nicola Rainbird got married at a private ceremony in East London. While he described the marriage as a performance art piece, the decision was partly due to fear he might be deported as he’d been arrested for having sex in a public toilet at Liverpool Street train station.

Bowery and Rainbird’s partnership culminated in a performance in which Bowery ‘gave birth’ to Rainbird. Strapped upside down in a harness secured to Bowery’s body, Rainbird burst through his costume as he laid back simulating labour. Rainbird appeared to the audience naked, painted red and wearing a string of sausages as an umbilical cord. The performance became an integral part of Bowery’s act.

Bowery’s band Minty, formed with ex-designer Richard Torry and then later expanded to a full live band, provided Bowery with a new outlet for his artistry. The performance of their song ‘Useless Man’ featured the ‘birth’ scene and explored ideas around sexual desire, gender play, and how ‘uselessness’ could be a productive position.

As well as the ‘Birth’ performance, Bowery and Rainbird would enact other bodily functions during Minty gigs (apple juice standing in for urine, pea soup for vomit). Presented at a time when fear around AIDS was at its height, by staging these messy parts of life Bowery wanted to challenge and celebrate all aspects of the body.

Bowery died on New Years Eve 1994, at the age of 33, from an AIDS-related illness. A person who incited shock, disgust and joy, his body modifications and provocations sought to question and test all boundaries in art and life. Resisting all forms of definition, Bowery’s work pushes us to look into our own mirror and move beyond appearances, to embrace the unknown.